We have a weekend default. When there’s nowhere else we feel the need to be, we go to the Dead Zoo .

It’s officially the Natural History branch of the National Museum of Ireland. But why would anyone bother to call it that when it has such a nickname?

You can go check out the history of the place. They have a website. I just want to talk about the sheer, decidedly bizarre fabulousness of the place. It’s the first museum I ever visited in Ireland, decades ago, and the first place I always wanted to visit when I came on subsequent visits. When Himself and I talk about the thousand ways we might never have met (the story of how we did meet is actually pretty good and might be fodder for another post), I occasionally wonder… His dad used to take the four Himself siblings to the Dead Zoo on the weekends. Maybe, just maybe, on my first visit, they were there… Nah. But it’s a nice thought.

Anyway. It’s this wonderful old, purpose-built Victorian pile near Merrion Square. And other than some invisible structural renovations a few years ago, it hasn’t changed in, well, forever. You can practically hear the ladies’ silk skirts swishing. I can’t find any record that Oscar Wilde ever visited, but he must have. Betcha he loved the cheerful, macabre, OTT splendor of it. It looks like this:

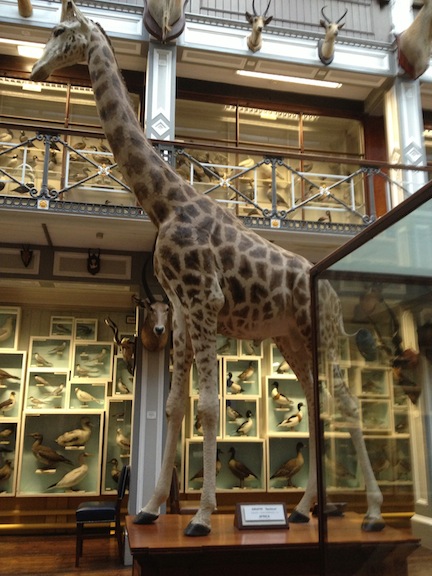

It’s jammed, literally to the rafters, with hundred-year-old, moth-eaten (or formadehyde-flaking), often-snarling, preserved dead things. Creepy? Icky? Absolutely, when you think about it that way. Madam moves more quickly past some exhibits than others. Like the Irish wolfhound that was someone’s pet and the polar bear with the very visible bullet hole in its head. (Yes, really. Not one of the more attractive specimens.) But then, maybe that’s part of why my soft-hearted family doesn’t hate the place. It’s unapologetic; this is a dead zoo, after all. Doesn’t pretend to be anything else. You come here to see the specimens up close. You used to be able to stand virtually under the overstuffed hippo and giraffe and see the stitching. That giraffe is gone, replaced by a newer, leaner, Spotticus.

Ironic that the museum’s mascot is the youngest thing there. Another element that mitigates the “ick” factor is that virtually nothing in the place is less than a century old. And again, unapologetically, everyone looks their age.

There’s some amazing, amazingly odd stuff, like this taller-than-me sunfish:

And some odd beauty:

Some history. Like the museum’s most famous residents: the ancient Irish Elk (Megaceros giganteus–love that name).

Apparently there’s a dodo skeleton somewhere out of view. I’m not sure why it’s not on display. Value, maybe? I can’t imagine the museum security is all that state-of-the-art. It’s not guilt or sadness for having something endangered or extinct. Those elk are long gone.

This is, to me, the saddest exhibit there:

Not the koala, although one can only imagine what was going through the mind of the Great Koala Hunter who faced down and bagged this one. “Those evil eyes! Those razor teeth! Our very lives depend on taking it unawares…” I would love to think this, along with everything else, went peacefully in its sleep years after announcing its intention to donate itself to the museum. Denial can be a lovely thing.

Not the koala, although one can only imagine what was going through the mind of the Great Koala Hunter who faced down and bagged this one. “Those evil eyes! Those razor teeth! Our very lives depend on taking it unawares…” I would love to think this, along with everything else, went peacefully in its sleep years after announcing its intention to donate itself to the museum. Denial can be a lovely thing.

The one that really breaks my heart is the koala’s doglike neighbor.

Warning: soapbox ahead. That is a thylacine, alternately known as a Tasmanian Wolf or Tiger. The last known thylacine died in a London zoo in 1936 of exposure. It was neglected and froze to death. We visit the thylacine whenever we go to the Dead Zoo and I, in typical (or maybe just my) obnoxious parental fashion, try to make a learning moment out of it. It was no secret in 1936 that thylacines were on their way out, that there was only a handful left. We could have saved them. (On a very slight tangent, David Attenborough’s most recent, wonderful special, Attenborough’s Ark, is about saving endangered creatures. And in several cases, he shows how individuals, literally one person, are doing it.)

Maybe I’m putting an unecessary burden on my kids, but I figure if they think about this dusty, sweet-faced thylacine in the glass box, maybe they’ll help save something else, like rhinos, before it’s too late. The sign attached to this one tells viewers that the horns are missing because there’s a danger of their being stolen to be ground down for ineffective but crazily lucrative medicine. Prosthetic horns are in the works.

Yeah, yeah, I know. Enough preaching. I leave you on a note of quirk. I like doing that, too. So I give you…